Lately, I have been in several meetings surrounding the future state of Enterprise Architecture, therefore I wanted to take a moment and re-group and discuss the basics around tackling “Strategic Thinking”.

In my view, to be successful when planning for a “future state” of any mission-critical application it is essential to consider the long-term implications of the overall objectives from a business perspective. This does not mean a macro-level understanding of the details on “How” to implement an application component, nor limiting the scope, or focusing on risk – rather it is all about Enterprise Architecture.

There is no silver bullet, no magic wand – in the end you must define the problem, admit what you don’t know, and have a set of tools to get the answers in an effective and repeatable manner.

EA 101

An Enterprise Architecture (EA) framework is a repeatable, consistent methodology to classify the relationship between business and IT, (in simple terms). There are several “EA Frameworks” available depending on where you look, who you work for, and how you plan to apply them. Almost every large organization has attempted to create some form of Enterprise Architecture model, often aligning business services with a repeatable and consistent method of mapping IT-related characteristics to known business drivers.

Public sector agencies, departments and bureaus have traditionally been early adopters of the “EA Mindset” – principally because they have a requirement for accountability from a funding perspective, accountability being a known benefit of a solid and successful EA program. In most cases, the underlying foundation of many EA programs is TOGAF.

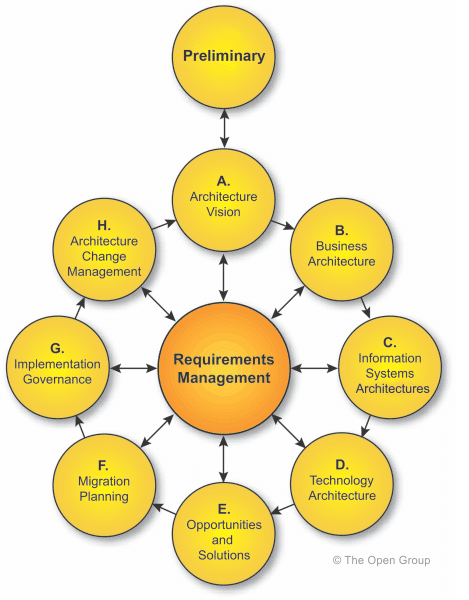

The Open Group Architecture Foundation (TOGAF) is a framework for designing, developing and implementing an Enterprise Architecture program within an organization. It is typically free of charge; however it is governed by specific terms of use. Like any other framework, it is a tool, not a silver bullet to solve existing business problems – it can be used to identify, categorize, classify and document an enterprise to ensure business service alignment to known investments and delivery capabilities.

It was originally founded in the mid 90’s (1995), based on a Department of Defense (DoD) Technology Architecture Framework for Information Management (TAFIM). The objective behind any EA framework is to answer one overwhelming question often overlooked, namely – “Why?”.

“Many organization treat EA as a rigid model; however in my opinion EA needs to be flexible and answer one simple question – “Why are we doing this?”

– Rick Lapenna

While that may sound simple, the fact remains that many organizations make the mistake of not addressing that one simple question. Often time and energy is spent in project silos, which compete for corporate resources (funds, people, assets, etc).

All the effort is spent on perceived value – rather than understanding the difference between tactical business objectives and strategic business goals – the two are very different. In order to truly innovate you must understand the problem you are trying to solve in the first place – no single EA framework will give you the answer, merely a consistent process to finding it. Often this involves borrowing concepts from more than one framework, methodology or even technology in some cases.

Hybrid Approaches

If you follow the process outlined in any solid EA framework, (such as TOGAF), you will be able to identify the “Why Question” and potentially many more like it – such as when, where, what and who (often called the 5W’s), the “How“, is a by product of the 5W’s. Taking that approach may involve looking outside of the traditional TOGAF model as well, perhaps expanding the toolset to include Zachman, another commonly used EA framework. Ironically though, many projects will invest a great deal of money and effort in the “How” to deliver a system, but by the time it is implemented the “Why” is not longer applicable, nor is the value of the new solution realized – a case frequently of too little too late.

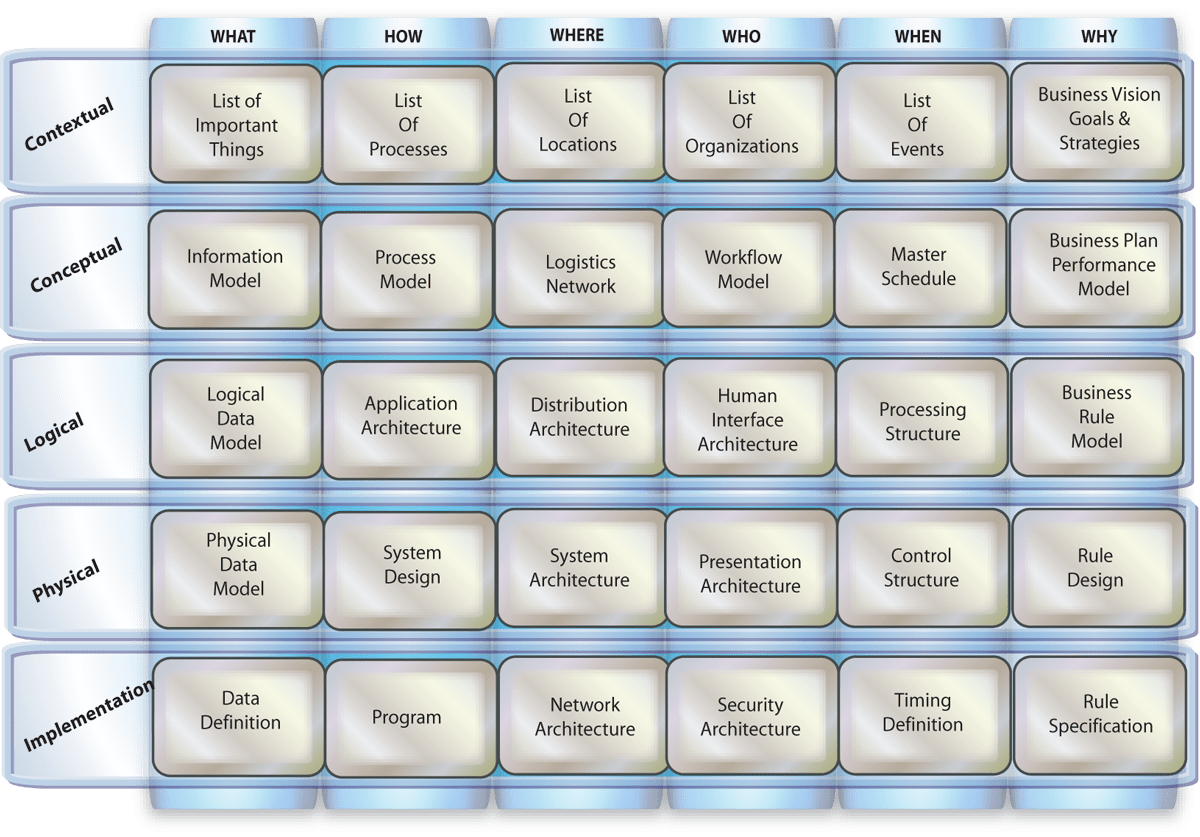

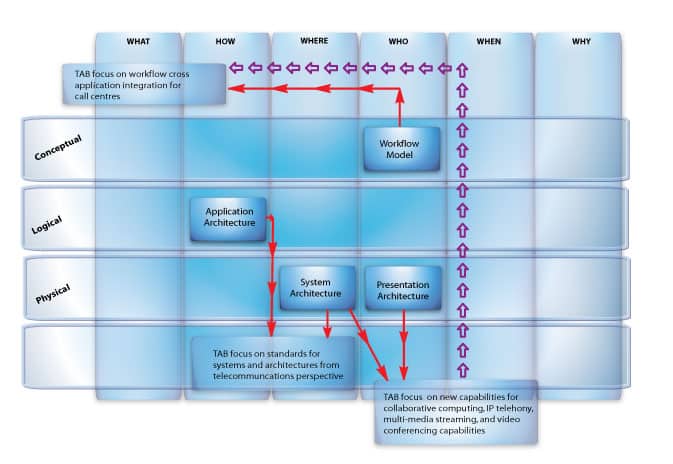

Under the Zachman model, it aligns these 5W’s across rows which deal with the “How” using a multidimensional grid. The EA process using this approach is called “Reification” – which loosely translated means, “Making it Real”. Zachman provides a consistent manner to various views of the enterprise, but it does not provide a canned process (like TOGAF), for populating them. Zachman assumes governance, process and compliance are present, and/or already applied.

Unlike TOGAF, Zachman is not so much of a formal framework, but rather a guide for capturing these 5W’s in a consistent manner. TOGAF is extremely focused on “Solutioning” within an enterprise, (some will argue that), while Zachman is more of a “Planning” tool to establish relationships between elements categorized into rows and columns. Rows are perspectives, (contextual, conceptual, logical, physical and detailed). Columns answer the 5W questions via cells which are the intersection between the row and column – the artifact or EA deliverable which answers the question in identified within the cell (for example – “System Architecture”, which is viewed in the “Physical” perspective within the “Where” column).

Critical success factors in defining an EA program may include facilitation and measurement – areas which are often overlooked in both Zachman and TOGAF; they really don’t focus on measuring success, but rather documenting the criteria to achieve it (EA assets). TOGAF, for example, does have a governance approach, but it may not be applicable for a given organization due to politics or corporate areas of responsibility – sometimes projects operate in silos which in turn create EA bubbles or micro chasms inside an enterprise.

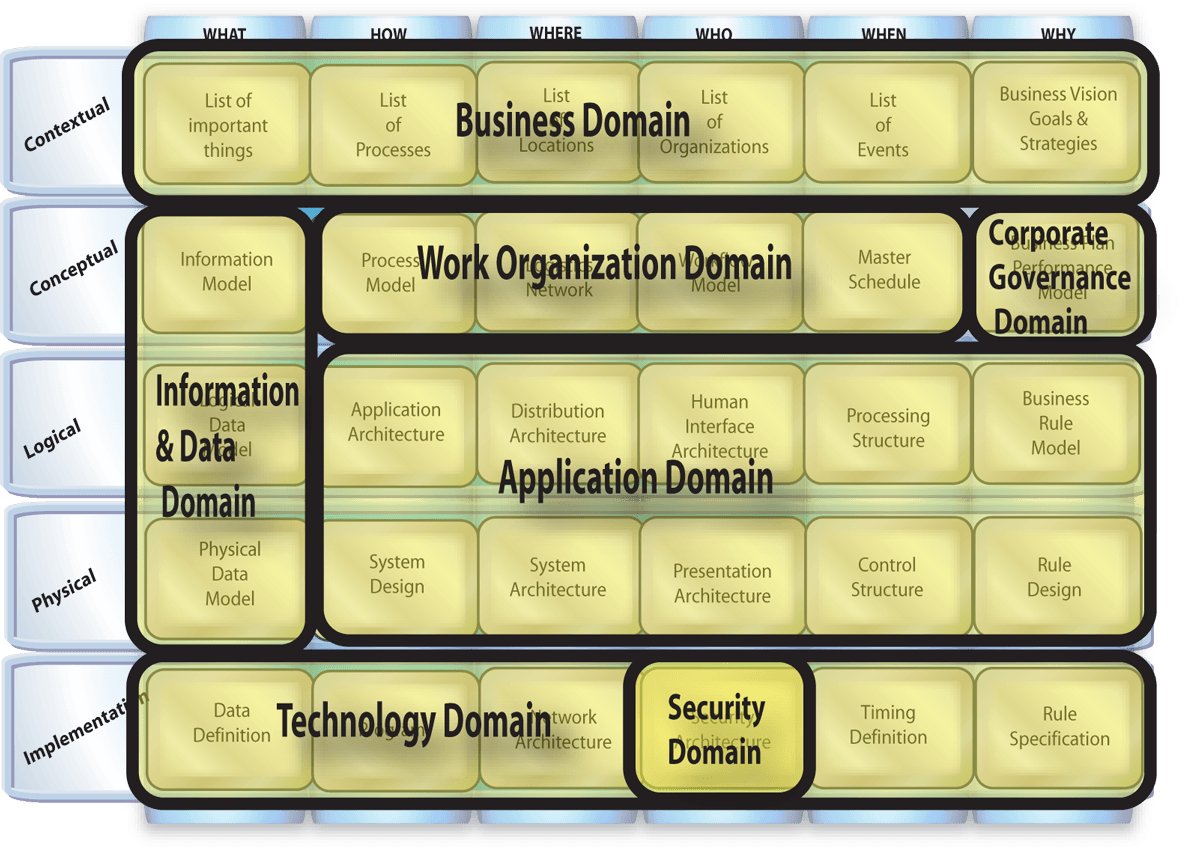

By blending models and creating high-level domains helps define which elements of which framework belong together so that they can be mapped consistently. It is for this reason that many organizations actually create hybrid frameworks, which take the best parts of both Zachman and TOGAF and blend them to create a tailored version of an EA methodology which can be applied across their enterprise.

Ideally, such hybrids may go so far as to include elements of other frameworks not related to EA, such as ITIL and/or Six Sigma to provide the governance and measurement criteria needed for their enterprise.

To ensure adequate alignment, the level of detail applied in the model must meet the minimum requirements of the framework for which it is mapped, for example, analysis should be consistent to map the domain correctly against the artifacts which support the domain/cell reference.

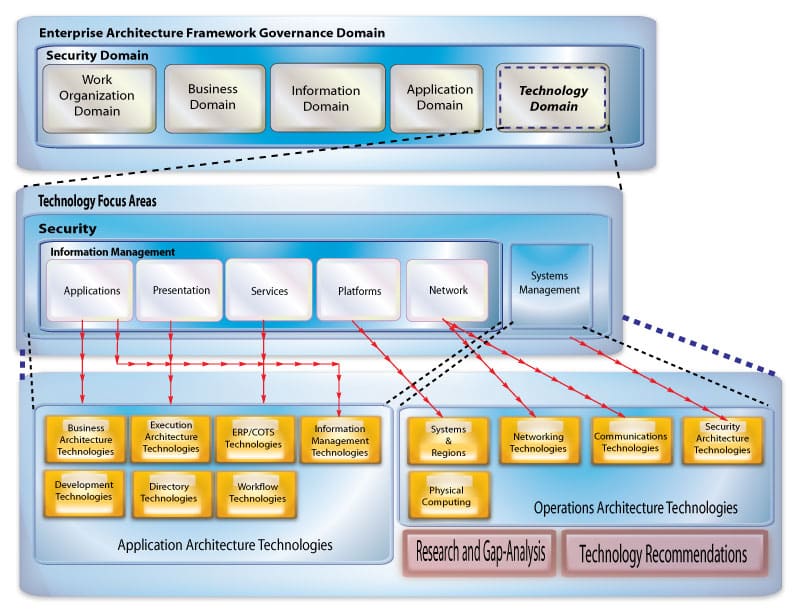

One approach is to develop a Technology Architecture Blueprint (TAB) which provides a context for mapping EA domains. This can be used as a starting point from which relationships can be assembled, more typically from the bottom-up rather than the top down. This creates an “As-Is” perspective of the enterprise by mapping existing investments against architectural cells and domains.

A focus on the TAB can provide a perspective which maps technology to business drivers in higher-level domains, and allows for the establishment of sub-domains, which reference components of technology. The objective would be to define the “Gaps” in order to make recommendations which re-vitalize the technology while still meeting the business need – often called the “To Be” targets from an enterprise perspective.

The ability to decompose high-level domains into discrete, focused sub-domains creates the ability to identify the technologies which support the business function. This is known as a Technology Reference Model (TRM). A “Call Center” would be considered an element of the Communications sub-domain of the TRM, which maps a relationship between the Technology Domain and the business functions which it serve. For example, a call-centre has a dependency on Workflow (WHO, from a Conceptual perspective), which relies on Applications (HOW), which are built from a Systems (WHERE), which also impacts the Presentation Architecture (WHO, from a Physical perspective). These relationships pin-point specific use-cases for a given technology component (or brick).

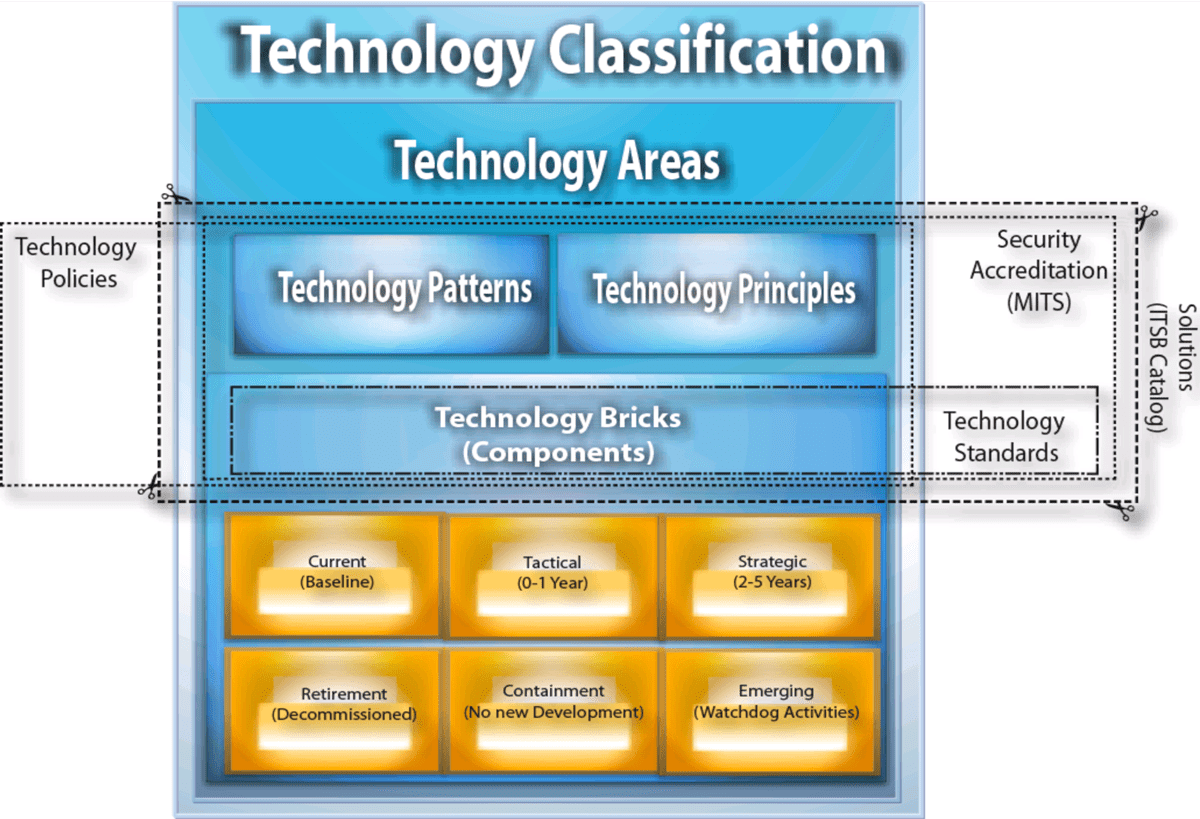

The model for a TRM supports this concept. The TRM should define a structure which maps to standard architectural domain model in a consistent manner. In addition, the TRM can also be the foundation for a Technology Roadmap, since investments in technology components (bricks) can be organized into categories for downstream requirements based on the capabilities of technology to business need it serves, (the To Be targets). Identifying the roadmap for a given technology allows for placement of that technology in a matrix which can classify the “fit” it has in the enterprise.

This placement can help refine a Service Reference Model (SRM), and can be used a fiscal forecasting tool within an IT department. By understanding how a technology is mapped can also influence other core EA dependencies which relate to security, standards and policies. Security accreditation being amongst the most visible when it comes to projecting business assets, services and intellectual property.

Strategies For Success

A very successful approach in many organizations is to tackle the development of an EA program from multiple angles in parallel. For example, defining EA domains which align with existing IT projects enables projects to assign owners for any given domain from the project’s perspective. The same is true for operations and sustainment, by aligning projects to domains and technology to applications these perspectives can be mapped into various reference models.

While there is often heated debate surrounding this approach over the adherence of any pure methodology or framework, the fact remains that without understanding how an enterprise has applied it’s technology investments will continue to put EA models into a “theoretical” box, which can seriously impact the adoption of an EA model, and subsequently reduce the perceived value of the overall EA program.

Making EA “real” requires an understanding of how technology is mapped to existing solutions to ensure perceived value …

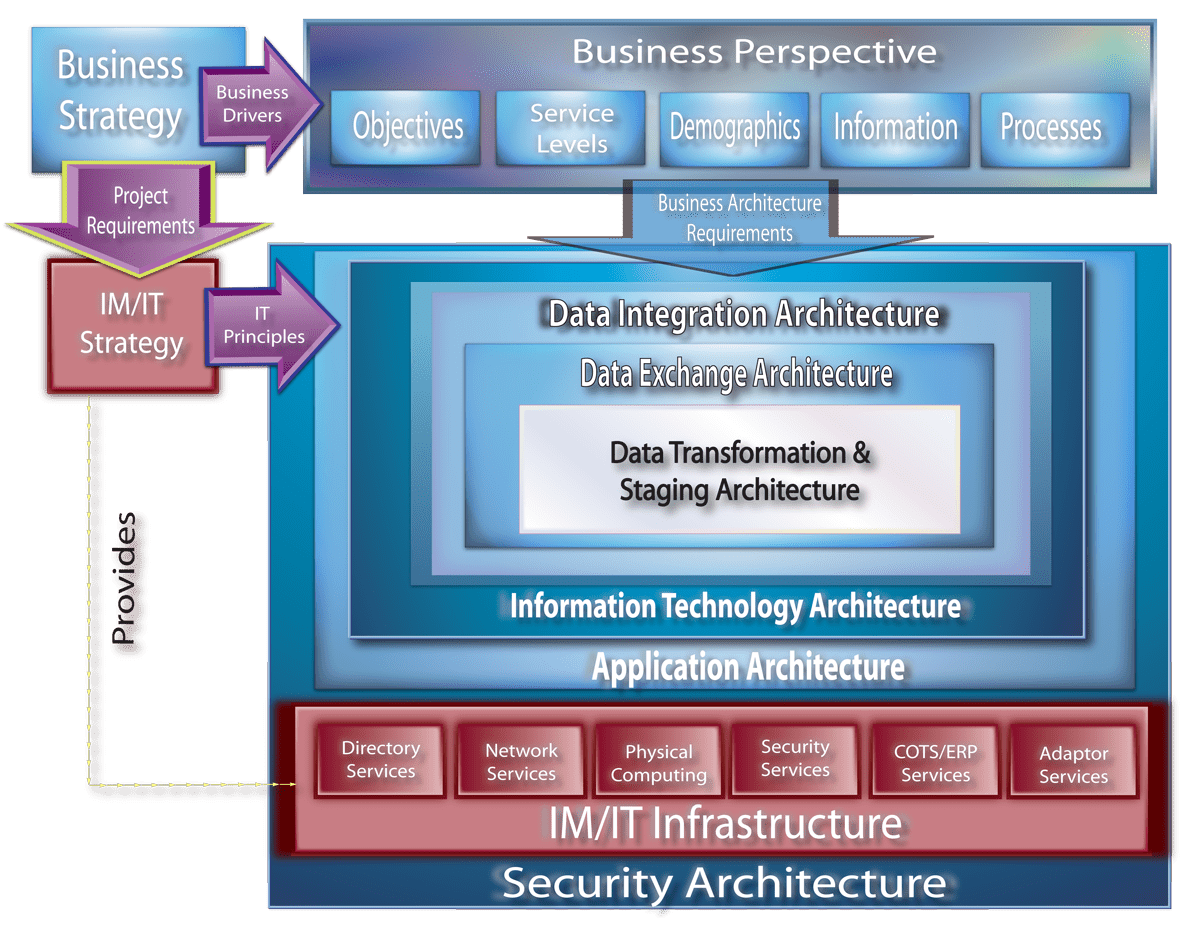

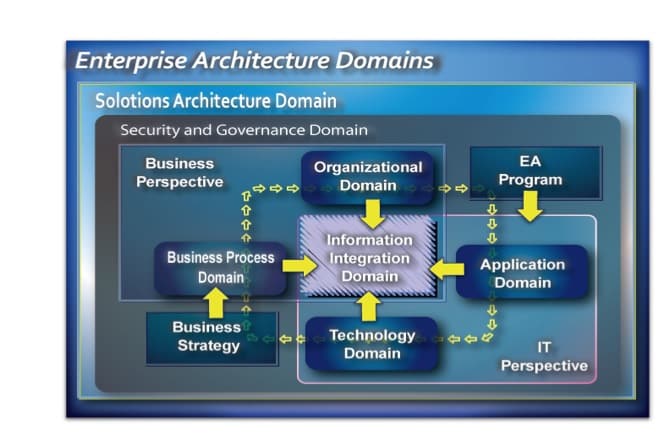

Traditionally, EA has been viewed in two distinct ways, the perspective of the Business and that of IT. Business Strategy drives the business process, which in turn impacts the Organization, which defines EA goals, which drives Applications (Solutions), which supports the Business Process, which in turn leverages Technology. The intersection between all the domains is Information, which is at the heart of any enterprise.

An example for viewing the relationship of this hybrid-model may consider aligning EA domains with aspects of the contextual, logical and physical perspectives to ensure a mapping for a given technology.

Often, organizations elect to develop business models in parallel with reference models (technology or service), so that under a framework (like TOGAF for example), multiple perspectives can be viewed which make sense to the various consumers of the EA repository. Which is an important point, the EA Repository; the warehouse for EA artifacts, standards, policies, governance and planning.

EA Repositories

In my opinion EA should be evolutionary and should drive innovation across an enterprise. To achieve this goal the influence of an EA program has to extend into service delivery, furthermore it is critical that such information is made readily accessible in a presentable forum. There are various ways to tackle this, which range from complex custom-developed portals, to COTS-centric tools. No matter which approach is taken, the bottom-line is that the information must be easy to access, well understood and provide value to the business.

Tools that provide Enterprise Portfolio Management (EPM), like Troux for example have tremendous capabilities to promote EA assets within an organization; however even a tool as robust as Troux will have limited impact on projects and initiatives unless it’s value is communicated.

The ability to link EA artifacts to solution development and delivery is the key. The Troux product provides this capability via a an integrated set of components.

Like any tool, the ability to keep information current is essential in order for that information to be seen as valuable. This is where many organizations run into issues, the people that use EPM technologies and those who need to consume them are often at opposite ends – there is a requirement to view the same data in different perspectives which makes the information either relevant and not esoteric.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) has done an amazing job at creating a portal that does exactly that. In 2005 they created an online portal to promote EA across NIH. The portal has been seen as a model for implementing EA, since it integrates all of the cornerstones of a sold EA program – communication, standards, compliance, governance and relevance.

The most powerful aspect of what NIH has done is the ability to link a technology Reference Model with a Technology Roadmap. This empowers the business, project teams, vendors and virtually every aspect of their IT enterprise.

From EA to Innovation

I read a great article the other day from the Harvard Business Review (by Greg Satell – Before You Innovate, Ask the Right Questions). It dealt with the concept of applied innovation (and ironically EA in a sense). The article took the position that true innovation cannot be achieved using a traditional model (like EA), since they often do not really define the “Problem” they are trying to solve. It quotes Albert Einstein …

“If I had 20 days to solve a problem, I would spend 19 days to define it.”

– Albert Einstein

Which I happen to agree with. In the many years I have spent working in EA, I continually ask myself those same questions – ‘What was that problem again …”? We sometimes can get so caught-up in the methodologies and frameworks that we forget what real EA is all about, which is, in my opinion Innovation.

The article points out that the problem is either well defined, or not well defined. The domain in which it resides is either known, or not really known – in other words we tend to “Guess”. By placing the problem in a matrix like this one, it seems very simple and very clear to me. Before I try to map anything to anything, understand the Why, define the problem, then obtain the right level of detail to quantify the type of innovation which can be applied to any EA model.

The approach I put forward in this article attempts to reduce the amount of guess work by developing an understanding of the current IT investment as a starting point and working EA from the bottom-up and not the top-down. This is especially true for large enterprises where there is an existing legacy application portfolio.

At the end of the day, I firmly do not believe any one framework is a silver bullet, they are tools that we use to understand our business, the technologies which support the business and the manner in which they have been applied – with an end-game of driving our ability to innovate.